Written by: Amy Hein, Director of Scientific Workforce

Over 10 years ago, I had an opportunity to attend a training on the book Crucial Conversations. I found the content completely changed my approach to handling difficult conversations, and, more broadly, to problem solving within teams.

What are Crucial Conversations?

A crucial conversation, simply put, is a discussion where stakes are high, opinions vary, and emotions run strong. When all three of those factors are present in a conversation and it turns crucial, it’s important to start with dialogue and work to create a shared understanding of the issue. With opposing opinions, it’s easy for each side to have a different interpretation of the facts and to see the critical issues differently.

Key Concepts

The pivotal perspective change for me involved four key concepts that I’ve paraphrased here:

- Focus on what you really want

- Avoid the Sucker’s Choice

- Make it safe

- Stop telling stories

Focus on what you really want. My colleagues have probably heard me ask in meetings, “What is the real problem we are trying to solve?” It’s easy to become focused on the symptoms of a problem or the most urgent items, but not the underlying root issue. For example, a colleague and I were recently discussing the best way to show expenditures on a monthly report. We had different opinions about what would be clearest, and weren’t finding any effective middle-ground solution. After several meetings, I finally stopped and asked myself: What do I really need in this situation? I realized I needed three things: 1) To meet contractual obligations, 2) to meet client desires, and 3) to minimize time to complete the reports. I went to the original contract , re-read the actual requirements, and checked what else we were providing to the client. With that information, I went back to my colleague and the client and proposed a new, alternate approach that reduced the number of reports we submit by half and removed the most error-prone section. Stepping back to reevaluate my true purpose for the conversation helped re-focus our group on a shared purpose, and helped create an entirely new solution.

Avoid the Sucker’s Choice. After you find the root cause of the problem and re-focus on what you really want, it becomes easier to avoid the dreaded Sucker’s Choice. The Sucker’s Choice is a dilemma in which you feel like there are only two opposing options and by choosing one, you can’t have the other. To expand on the expense reports example above, my initial thinking before we resolved the issue was, I can either graph the expenditures the way I want, going against my colleague’s opinions, or I can leave the report as is, error-prone and redundant. This was a Sucker’s Choice: pitting two desired outcomes against each other, and assuming this was an inevitable trade-off. By stepping back and determining the underlying goals, however, we moved from an “either/or” to an “and” choice, where both desired outcomes are possible. Challenging my assumption about what was required in the contract allowed me to consider other options and find a third, better solution.

Make it safe. At Ripple Effect, we talk a lot about emotional intelligence, and for good reason. To work smarter and perform better, we have to manage our emotions and handle interpersonal relationships with empathy—and crucial conversations are all about emotional intelligence. A key ability in any crucial conversation is being able to recognize when the other person is feeling “unsafe,” or defensive in the conversation, and then taking quick action to bring the discussion back to a safe place. When people feel attacked or defensive on a topic, the dynamic changes to “us against them” and that shared meaning and shared goal is forgotten. I’ve been amazed at how far an apology or reframing of a misinterpreted statement (“I didn’t mean to say X; what I meant was Y”) can go a long way toward keeping a conversation calm and productive. Use your emotional intelligence to keep an eye out for when safety is threatened, and work quickly to reestablish it.

Stop telling stories. Finally, when having crucial conversations where emotions run high, it’s easy to automatically jump from the facts of the situation to the story you tell yourself about the other person’s motivations and beliefs. These stories are often based on assumptions, fair or not, and often dictate the actions we take. They are also frequently wrong. When I find myself preparing for a crucial conversation, I stop to ask myself, “Why would a reasonable, rational person hold this opinion?” Identifying when we are telling stories and making assumptions about the situation, taking a step back to return to the facts and then talking with the other person to learn their true story will result in a more productive conversation.

One of the best ways to persuade others is with your ears, by listening to them. –Dean Rusk

There are many great approaches in Crucial Conversations; the four I described above resonate most with me, but depending on your own relational strengths and blind spots, other approaches may be more helpful to you. I hope you find them as valuable in your professional and personal life as I have.

Mastering Crucial Conversations

After introducing the four key concepts we discussed above, Crucial Conversations then discusses the process for mastering crucial conversations. The book unpacks each item and provides many examples, showing each principle in action. I’ve provided a high-level outline of the key takeaways below.

Start with Heart: Work on you first. Focus on the right motives and stay focused on those, no matter what happens.

- Focus on what you really want.

- Refuse the Sucker’s Choice (avoid either/or choices.)

Learn to Look: Look for when the conversation becomes crucial.

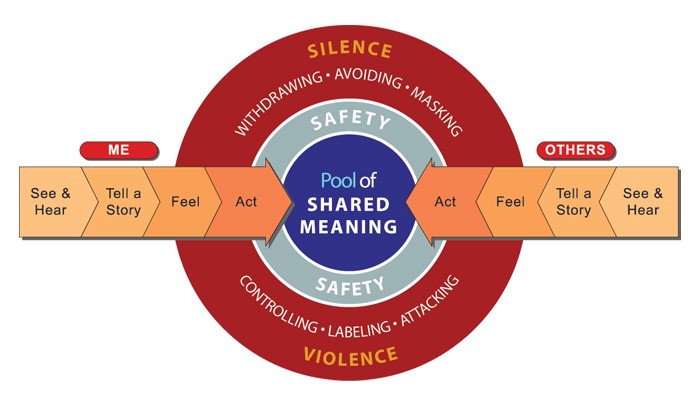

- When things become unsafe, people move to silence or violence.

- ‘Silence’ behaviors include: Masking, avoiding, withdrawing.

- ‘Violence’ behaviors include: Controlling, labeling, attacking.

Make it Safe: Establish mutual purpose and maintain mutual respect. We all want to have a positive outcome. To get back to safety:

- Apologize when you’ve violated respect.

- Contrast to fix misunderstanding. Contrasting is a don’t/do statement that indicates you don’t mean to disrespect them, but you do want to address the underlying issue. For example, “I don’t mean to indicate that you are not a hard worker, but I do need to have this report by Monday.”

- Find mutual purpose. Work to identify the underlying goal that is common between you. If none exist, invent mutual purpose by moving to more and more encompassing goals, e.g., “We all want this project to be successful.”

Our stories create our emotions and we create our stories. Analyze your stories and get back to the facts.

Master My Stories: Separate fact from story and tell the rest of the story. Consider why a reasonable, rational person would hold the opposing opinion. The pathway to action can be broken down into multiple steps:

- See and Hear: First we observe what others do

- Tell the story: Based on the facts we observe, we tell a story about why someone else is behaving in that way

- Feelings: The story we tell ourselves about the other people involved drives our emotional reaction and the feelings we have in situation

- Act: Finally, our feelings drive our actions

STATE My Path: Follow this pneumonic to:

- Share your facts

- Tell your story

- Ask for others’ paths

- Talk tentatively

- Encourage testing

Explore Other’s Paths: Ask yourself “Am I actively exploring others’ views?” and “Am I avoiding unnecessary disagreement?”

- Ask, Mirror, Paraphrase, and Prime (AMPP): Ask to get things rolling, Mirror to confirm feelings, Paraphrase to acknowledge the story, and Prime when you’re getting nowhere.

- When it’s your turn to talk, remember your ABC’s: Agree on important points; Build by pointing out areas of agreement, and then add elements that were left out; and Compare by describing how your ideas differ rather than theirs being wrong.

Move to Action: Decide how you will decide, document the decision, and follow up.

- Dialogue is not decision-making.

- Review the 4 Methods of Decision Making and evaluate for your situation: Command, Consult, Vote, and Consensus.

- Determine who does what, by when.

Resources

Here are some additional resources and training modules if you are interested in learning more:

- Crucial Conversations Review

- Crucial Coversations Cliff Notes

- Introduction by Joseph Grenny

- What is my motive? by Candace Bertotti

- What is the real problem I’m trying to solve? by Mark Carpenter

- Path to Action by Salomeh Diaz

- Start with Heart by Beth Wolfson